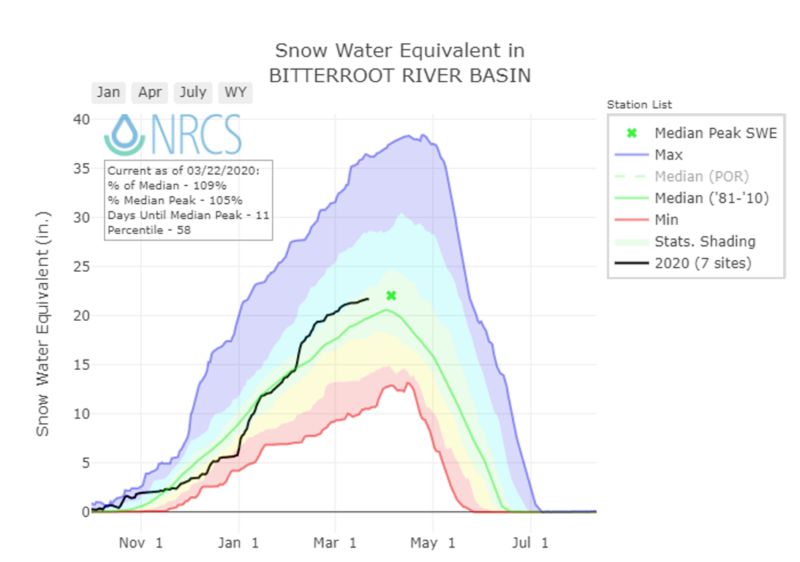

This month’s snowpack update comes as we transition from winter to spring. As of March 22, the Snow Water Equivalent (SWE) totals in west central Montana are just above average (Figure 1). After a month of small storms and average temperatures, our primary avalanche concerns are focused on snow at or near the surface of the snowpack. This update summarizes the events that got us here, and provides an outlook as we head into April.

Weather Events

Our biggest storm event in the past month occurred between February 23 and 25. We received 6-12” new snow, which fell on a myriad of surfaces including old crusts, surface hoar, and near-surface facets. Snow totals equaled .6-.8” SWE.

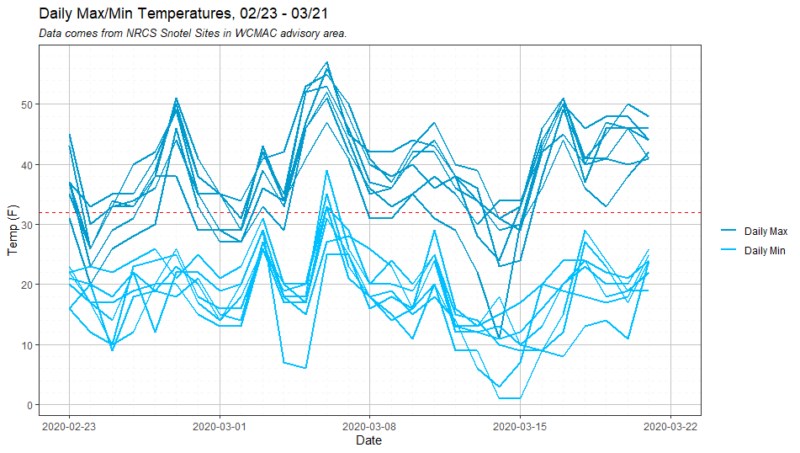

The next pulse of moisture came on March 3-4, dropping 3-10” of snow with strong winds. This storm was immediately followed by a rapid warming event from March 5-7, with daily high temperatures climbing above 50°F and lows staying above freezing on the night of March 6 (Figure 2).

A weak system favored the northern mountains on March 11, dropping 4-6” of snow in the Rattlesnake and Seeley Lake areas and leaving most of the Bitterroot high and dry. Snowfall picked up again march 13-15, with close to a foot of snow in the Seeley Lake area and 4-6” elsewhere. This storm came as a strong low pressure system passed to the south, which resulted in unusual easterly winds in the northern half of our advisory area.

Avalanche Activity

The combination of moderate, consistent snowfall and seasonably warm temperatures has helped our snowpack gain strength. Since our last snowpack update, we have not received any reports of avalanches failing deep in the snowpack in our advisory area. There were, however, some noteworthy cycles involving snow near the surface of the pack.

The late February storm led to widespread dry loose activity along with some natural and human-triggered wind slabs. While a few of these avalanches were big enough to bury or injure a person, most of them were small and only harmful to skiers and riders in consequential terrain.

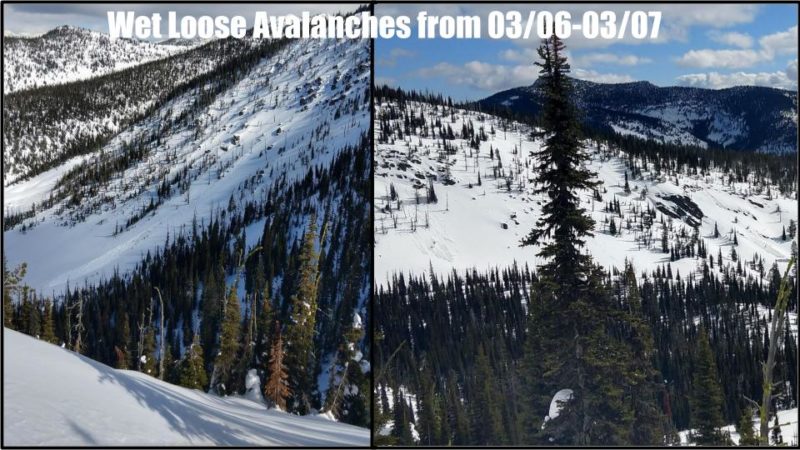

The next cycle came during the warm spell in the first week of March. Three consecutive days of warm temperatures during the day and above-freezing temps at night led to widespread loose wet avalanches throughout the area. (Figure 3).

Temperatures returned to normal by March 8, and our next round of activity came with the new snow and easterly winds on March 13. Strong easterly winds at the onset of the storm subsided by the time snowfall really picked up, which minimized the development of wind slabs and resulted in primarily dry loose avalanches in steep terrain across the advisory area.

Over the past month, and especially in the past two weeks, we have seen increased glide avalanche activity in the Bitterroot (Figure 4). Exact timing of glide avalanches is difficult to predict. However, there are some characteristics that are consistent in most glide activity, and the cycles in the Bitterroot this season have been no exception. Glide avalanches fail when the entire snowpack slides on a low-friction ground surface. This can be due to vegetation, soil, or in our case, geology. Although glide avalanches can occur any time during the winter, they are most common in the springtime when liquid water is present at the base of the snowpack. All of the glide avalanches we have seen so far are failing on smooth granite slabs that are lubricated with meltwater. Before the slab releases, a glide crack (photo) will open up as the snowpack slowly moves downslope. These cracks can be present for days or weeks before the slab releases, so the best practice is to avoid travelling on or below these monsters.

Figure 4: Glide avalanches in the Southern Bitterroot, March 12. Photo: J. Lonn

Outlook

As we head into April, we need to keep an eye on two different groups of avalanche problems. The first (and easiest) is anything failing near the snow surface. With new snow, winds, and warm temperatures, we can expect to see more wind slabs and loose snow (wet and dry) avalanches over the next month. Dry loose and wind slab avalanches are relatively easy to predict, and will gain strength within a few days after a storm. Similarly, it is easy to anticipate the onset of wet loose activity as daytime temperatures warm above freezing and the sun comes out. They will be preceded by clear signs of decreasing stability like rollerballs, pinwheels, and sinking up past your boots in sloppy snow.

There is more uncertainty with the persistent weak layer near the bottom of the snowpack in the Southern Bitterroot. This weak layer has been with us all season, and it has been dormant since the last avalanche over a month ago. However, these deep persistent weak layers are capable of becoming reactive in the spring, even after weeks or months of no activity. There are two things that will increase the likelihood of seeing a large deep slab avalanche cycle this spring. The first would be an unusually large storm that loads the snowpack past its breaking point. This late in the season, we would most likely need several feet of snow to apply a big enough load. The other scenario involves liquid water. The deep persistent weak layers will be suspect after the first spell of two to three consecutive nights of above-freezing temperatures, or with a single rain event. Liquid water in the snowpack can decrease the strength of the already fragile weak layer, leading to wet slab activity failing near the ground.

Summary

After a month of near-average temperatures and modest snowfall, we have a generally strong snowpack in West Central Montana. There has not been a major avalanche cycle since our last snowpack update in February, and I do not expect another one unless we get a major loading event, a rapid warming event, or rain. For now, the main concern will be focused on how the snow is behaving at the surface. Watch for wind slabs and dry loose activity any time we get new snow, and monitor the potential for wet loose avalanches as temperatures rise and the sun comes out.

Thank you to everybody who has shared their observations with us throughout the season. Your obs are an integral part of the forecast. If you want to share what you see while you are out, you can send us an email at [email protected] or use the observation form on our website. Ski and ride safe!