Good morning, this is Jeff Carty with the West Central Montana Avalanche Center on Thursday, April 8, 2021. Regular avalanche advisories with avalanche danger ratings have ended. This does not mean the end of avalanches. Spring storms and warm temperatures may make avalanche danger rise. We will continue to post public observations, so please keep submitting them as you get out in the mountains. Below are a season recap and review of common spring avalanche problems.

We issued our final avalanche advisory for the 20/21 winter season on April 6, 2021. It caps a busy and challenging season. A proliferation of faceted layers and spatial variability made forecasting and recreating safely a challenge this year.

We issued our first avalanche advisory on December 1st this year in response to higher than average backcountry use, and enough snowpack to create avalanche conditions. In total, we issued 63 forecasts this year. Underlining the challenging conditions, only 6 were low hazard days, 5 in early December and 1 in March. Conversely, we issued 5 avalanche warnings, had 12 days of high hazard, 18 of considerable. This meant that 30 out of 63 forecast days this year had elevated avalanche hazard. Facets featured as a problem layer in almost all forecasts this season. The January 13th crust, created by rain to 8000’, featured as a prominent problem layer that contributed to faceting within the snowpack.

Despite conditions that we usually associate with bonding and rounding in the snowpack, such as warmth and depth, facets and persistent layers continued developing and propagating in tests. This added complexity and was compounded by drastic spatial variability. Stability varied widely over short distances, from drainage to drainage, and aspect to aspect, making both forecasting and risk management a challenge.

Weather Recap and Outlook

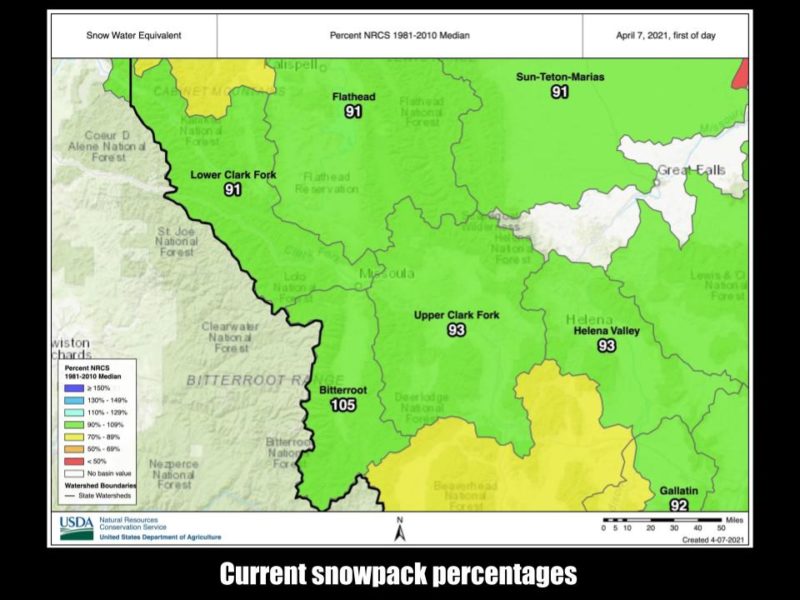

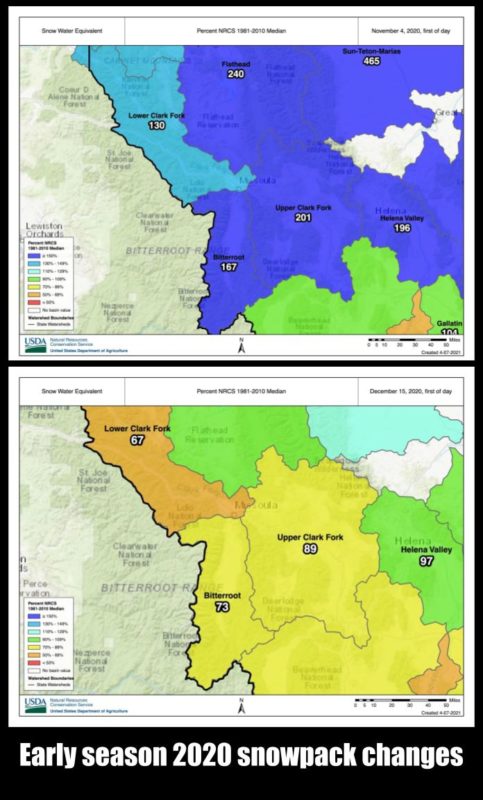

The weather contributed to the challenging conditions this year. Despite La Niña, abundant early season snow and predictions of heavier than average snowfall, it felt more like an El Niño year. In early November, the snowpack throughout the advisory area was 201% of average. However, the region experienced above-average temperatures and lower than average snowfall in December and January. Drought conditions reduced the snowpack to 89% of average by early December, and depth hoar began to form. By late January, snow totals dropped as low as 80% of average. February brought snow, and we received up to 12″ of SWE or roughly 120” of snow. The snowpack rose above 110% of average. Following a warm March with lower than average precipitation, we are currently sitting between 105% and 93% of the snowpack average.

Our first avalanche warning and high danger rating on December 20th were in response to loading on top of facets and crusts. This pattern was repeated 4 more times throughout the winter. January 13th delivered rain to 8000’ and created an ice crust that formed facets around it. This layer lingered throughout the region and contributed to the persistence of the facets in the snowpack. This layer was likely the culprit in the Lost Horse slide on February 21, 2021, that ran full path.

Finally, the last week brought 72 hrs of above-freezing temperatures to the mountains. This period underlines the unpredictability of forecasting wet snow problems. Despite a snowpack saturated to ground, and intense sun and warmth, conditions that often result in very large wet avalanches, we did not see a significant avalanche cycle.

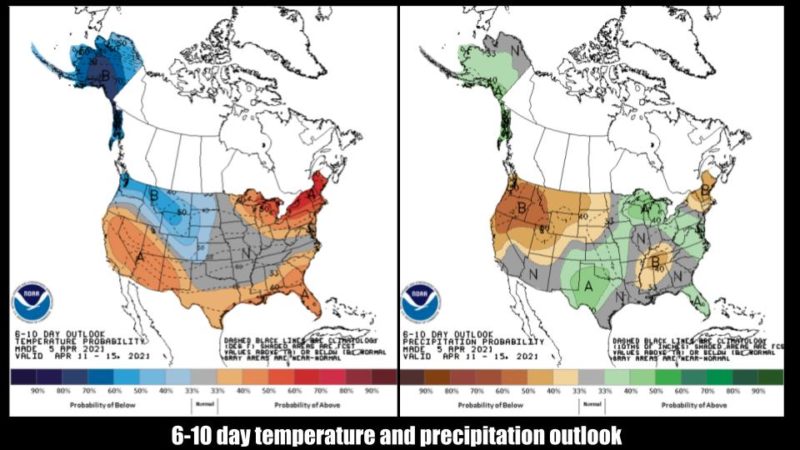

What does the rest of the season hold? NOAA predicts cooler than average temperatures with lower than average precipitation over the next 10 days. This likely means cold nights, clear skies, and warm days. Good conditions for corn skiing, and easier conditions for avalanche management. The one-month outlook shows west-central Montana with approximately average temperatures and precipitation for this time of year.

Spring Avalanche Problems

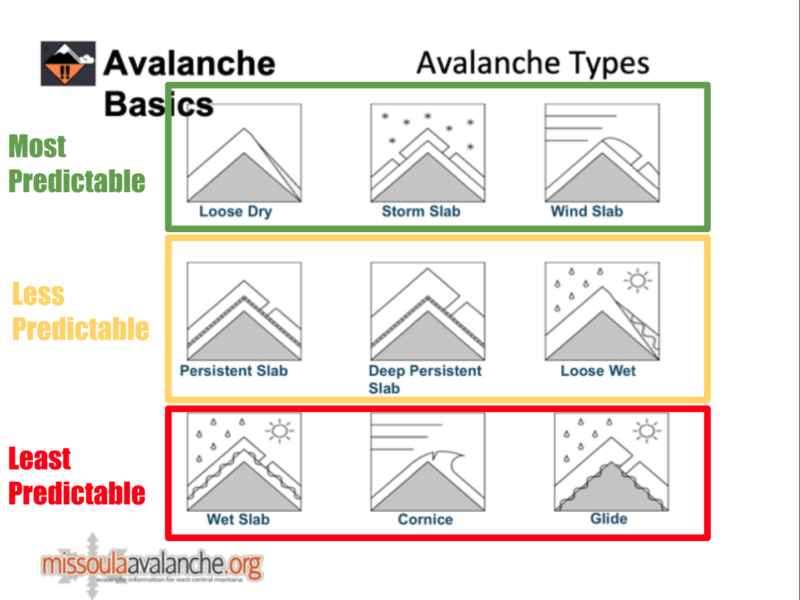

Spring can be a challenging time for avalanche conditions. Dramatic swings in weather and snow conditions are possible. As we’ve seen in the past week, we can move from mid-winter problems to wet snow problems within 24 hrs. Understanding avalanche problems can help us plan for successful days in the backcountry. You can read more about avalanche problems here.

We have a decent understanding and tests for dry avalanche problems. We know that propagations within a weak layer can travel horizontally under a slab, delaminating it from the bed surface in dry snow environments. If the slope’s steepness is enough to overcome the friction between the delaminated slab and bed surface, we get an avalanche. This is why the extended column test is such a good test; it gives us an idea of the propagation likelihood.

Wet problems have less understood mechanics and predictability. Standardized tests also become ineffective. As snow warms up, it loses cohesion, and water is introduced into the snowpack. The weight of the water can cause the release of wet loose or wet slab avalanches. Roller balls (pinwheels) indicate water in the snowpack and signal that the snowpack is losing cohesion. With continued warmth and water in the snowpack, we can get wet loose and wet slab avalanches. The rate of thaw that results in a wet slab avalanche is variable and unpredictable.

We know that the snowpack is stable when it is refrozen, and stability decreases as it thaws. With repeated cycles of daily freeze and thaw, called the diurnal cycle, the snowpack gets more dense and stable. With this pattern, instabilities become isolated to the upper snowpack that melts daily. This changes when we receive new snow that delivers a new load or have multiple nights with above-freezing temperatures that allow the snowpack to thaw to the ground and move moisture into underlying weak layers. Rain will also quickly destabilize the snowpack.

Without tests for stability assessments, we must rely on observations to make decisions. This method lends itself to all avalanche problems, often simplifying the decision-making process.

Trask Baughman, an educator with the West Central Montana Avalanche Foundation (WCMAF) explains:

With the conclusion of the 20-21 avalanche forecast season, you will have to gather and observe all necessary data to plan your adventures and make on slope go or no-go decisions. Bruce Tremper, the author of Staying Alive in Avalanche Terrain, writes, “good habits are what will save your life”. Having easy to use tools will help build those good habits and aid with decisions in the complex, dynamic mountain environment. All backcountry users, regardless of experience, can use rule-based decision-making.

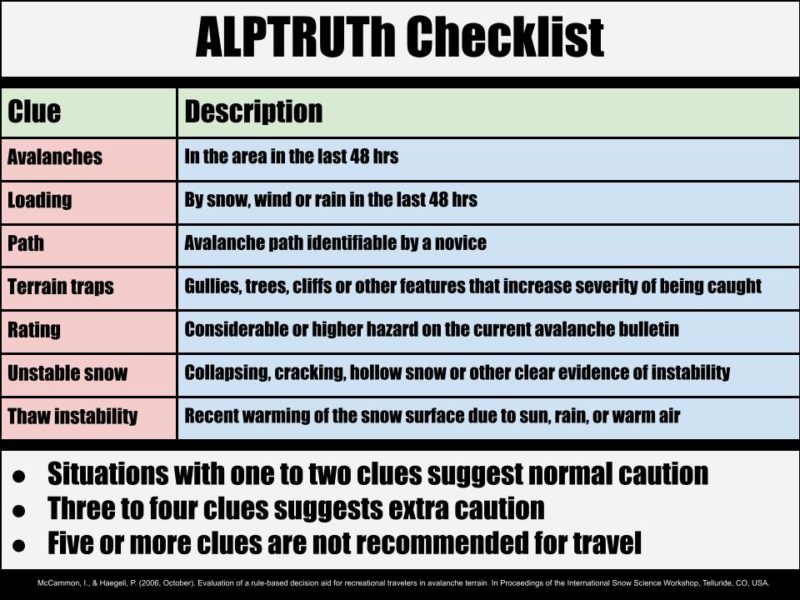

A powerful tool is ALPTRUTh, a mnemonic to help memorize and remember red flags and key terrain features. To utilize this tool, you note the factors and add them up. ALPTRUTh can be incorporated in a pre-trip checklist or a final check before committing to a slope. When 3 or 4 clues are present, extra caution and careful terrain management are needed (93% of accidents in North America have 3 or more factors present). If you have 5 or more factors present, it is recommended you push pause and carefully find an alternative path.

Avalanches, in the last 48 hours?

- Using resources like the Missoula Backcountry Facebook page and the WCMAC public observations page is an excellent place to find this information when planning your tour. When in the field, if you see avalanches on similar aspects and elevations that you want to ski, nature is screaming danger.

Loading, by snow, wind, or rain in the last 48 hours?

- Snow doesn’t like rapid changes; it takes time for it to settle and bond. Your pre-tour ritual should include looking at weather data for the last few days.

Path. Are you skiing an avalanche path?

- The “Path” in ALPTRUTh is for easily recognizable avalanche terrain. When choosing to ski avalanche terrain, it is essential to make sure no other factors are present and to use best travel practices like skiing one at a time.

Terrain Traps. Are there any terrain traps?

- Imagine the consequence of being caught? Any terrain features like gullies, trees, and cliffs will significantly increase the severity of being caught, even by a small loose wet slide.

Rating considerable or higher hazard on the current avalanche bulletin?

- Without an avalanche bulletin, assume the danger rating is Considerable. Only with careful consideration over days without significant weather change and no other red flags being present would I drop the danger rating to Moderate. Often in a spring diurnal cycle, the danger starts at low in the morning and rising throughout the day.

Unstable Snow. Has there been any collapsing, cracking?

- Like recent avalanches, collapsing and cracking are clear signs of avalanche potential. Careful decision-making and terrain choices are recommended.

Thaw Instability. Is the temperature rising?

- When temperatures rise above freezing, the snowpack’s cohesion quickly falls apart, leading to thaw instability. Keeping an eye on the time of day and rising temperatures is the name of the game in the spring. Looking at weather data to see if it is freezing at night will help give you a go or no-go decision before leaving your house.

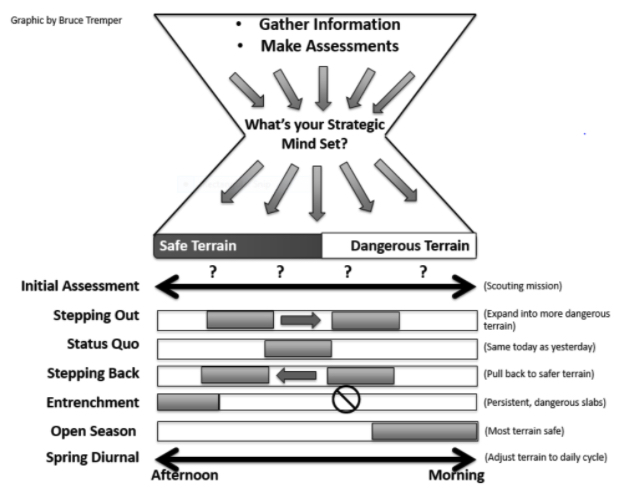

In my assessment continuum, I rely on observing red flags and weather trends that are listed in ALPTRUTh first and use data from snow pits last. If ALPTRUTh is indicating dangerous conditions then pits and stability tests are unnecessary. Stability tests do not reliably predict wet problems, and you should never use a single pit to make decisions when choosing to ski a slope. A quick hand pit can be helpful when investigating how saturated the snow surface is. Skiing a test slope is also a great way to gather information on surface conditions. When I decide that it is safe to ski avalanche terrain, I slowly step into more committing terrain in a systematic approach. Roger Atkins’ strategic mindset is a great tool, more can be read here.

The public observations page is a great asset to learn about conditions, but it is only effective if observations are being submitted. It may be more important than ever this time of year. Don’t feel obligated to submit complex observations, anything is helpful, and pictures speak a thousand words. Pertinent negatives are also helpful, if you didn’t see any red flags and found stable conditions, let people know.

Useful online resources:

- Weather

- The NOAA backcountry forecast page has a number of useful links including local SNOTEL sites.

- The NOAA home page also has good info, check out the discussion for more detailed weather information

- Montana MDT has Cams at Lolo, Lost Trail, and other roads, giving a visual on weather conditions.

- Snow-forecast.com Has good weather maps that show snowfall, freezing level, cloud cover, wind, ect.

Ski and ride safe. See you next year!